The word “jellyfish” tends to initiate a similar response in most people – “scream”, “run”, “this is going to hurt”. Being stung by a jellyfish is not pleasant and is something most would prefer to avoid. Our beaches warn us when they are out by flying a purple flag.

When exploring the seagrasses, this is not the first animal people thing they will encounter. Few associate jellyfish with the seagrass community. But within any community there are those we call residents (they reside here) and those we call transients (just passing through). It is the second group that we can place most jellyfish, at least the ones we are concerned about.

Photo: University of California

Jellyfish are animals, but not your typical ones. They are obviously invertebrates but differ from most others by having radial symmetry (having a distinct top and bottom, but no head nor tail). They possess ectoderm and endoderm (so, they have a skin layer and some internal organs) but they lack the mesoderm that generates systems such as the skeletal, circulatory, and endocrine. Though they do not have a brain, they do have a simple nervous system made up of basic neurons and some packets of nerve cells called ganglia. They seem to know when they are not in the upright position and know when they have stung something – which initiates the feeding behavior. But they are pretty basic creatures.

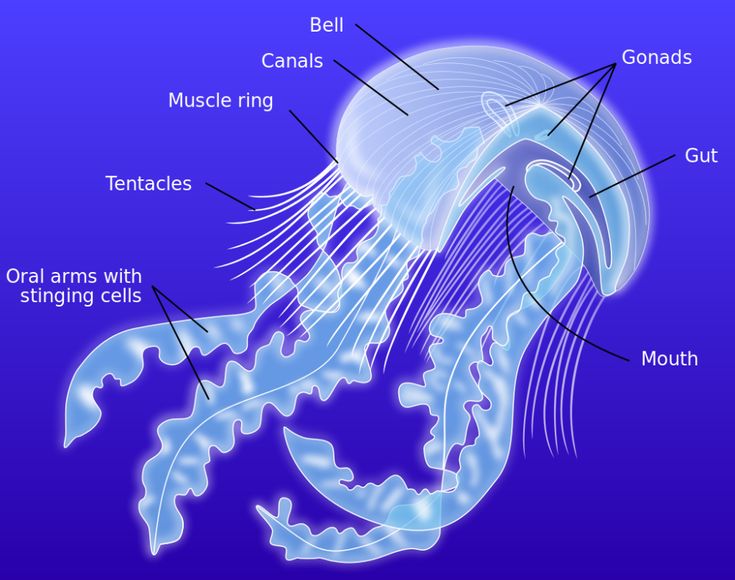

When you view a jellyfish the first thing you see is the “bell” and the tentacles – we always see the tentacles. The bell is usually round (radial), could be bell-shaped, or could be flat. It is made of a flexible plastic-like jelly material called mesoglea. Most of the mesoglea is actually water. When you place most jellyfish on the dock and come back in a few hours there may be nothing but a “stain” of where it was. It completely evaporated. There are some exceptions to this, like the moon jelly and the cannonball jelly, who leave thick masses of mesoglea for long periods of time.

If you look closer at the “bell” you will see shapes within the mesoglea. Some are stripes, and may have color to them, others look like a clover leaf. These are the gonads of the animal. Jellyfish are hermaphroditic (the gonads can produce both sperm and egg), and they reproduce by releasing their gametes into the water column when triggered by some environmental clue to do so.

Around the edge of the “bell” many have a thin piece of tissue called the velum that can undulate back and forth and allow the jellyfish to swim. Swimming can involve moving up or down in the water column, or turning around, but the swimming action is not very strong and the tide and current actually plays a larger role in where the animals go – like pushing them through a seagrass bed.

Under the “bell” is a single opening, the mouth, that leads into a simple gut (the gastrovascular cavity). This serves as the stomach of the creature. But there is no anus, when the jellyfish has digested its food, the waste is expelled through the same opening – the mouth. This is called an incomplete digestive system.

Jellyfish are predators and hunt small creatures such as baitfish. Though they know whether they are upside down or not, and may be able to detect light, most have no true eyes and cannot see their prey. Some species may be able to detect scent in the water and undulate their velum to try and move towards potential food, but most drift in the water and hope the tide carries them to dinner. To kill their prey, they extend tentacles into the water. These tentacles are armed with stinging cells known as nematocysts. Each nematocyst holds a coiled harpoon with a drop of venom at the tip. They are encased in a cell membrane and are triggered when an object, hopefully food, bumps an external trigger hair that will fire the harpoon. This will then trigger the release of many nematocysts and the potential prey will be “stung” by many drops of venom. The venom can either kill or paralyze the prey at which time the tentacles bring it to the mouth. Many jellyfish have venom that is painful to humans, like the sea nettle and moon jelly, others have a mild venom that we do not even notice. Some have a very strong venom and can be quite painful, like the Portuguese man-of-war which has put some in the hospital. The famous box jelly of Australia has actually killed humans. We do have box jellies in the Gulf of Mexico, but they are not the same species.

Photo: Brad Peterman

As the tide pushes these transients through the seagrass meadows, their tentacles are extended and small baitfish like juvenile pinfish, croakers, and snapper become prey. But there are resident jellyfish as well.

With the Phylum Cnidaria (the stinging jellyfish) there are three classes. Class Scyphozoa includes the bell-like jellyfish that drift in the water column with extended tentacles – what are referred to as medusa jellyfish. But there are two other classes that include benthic (bottom dwelling) jellyfish called polyps.

Polyp jellyfish resemble flowers. The “bell” part is a stalk that is stuck to a rock, pier, or seagrass blade. Their tentacles extend upwards into the water column giving the creature the look of a flower. Instead of drifting and dragging their tentacles, they hope to attract prey by looking like a hiding place or other habitat. The sea anemone is a famous one, and a good example of the polyp form. But it also includes corals and small polyps known as Hydra. Hydra are tiny polyps that are usually colorless and can easily attach to a blade of turtle grass. Here they extend their tentacles into the water column trying to paralyze small invertebrates that are swimming by or grazing on the epiphytes found on the grass blades.

Photo: Harvard University

Another jellyfish that drifts in the current is Beroe, what some call the “football jellyfish” or “sea walnut”. This a relatively small blob of jelly that lacks tentacles but rather has eight rows of cilia/hair (ctenes) along its side that move quickly and move this animal through the water. But like their medusa cousins, not against the tide or current. These jellyfish do not sting, they lack nematocysts, and hence are in a different phylum known as Ctenophora. Kids often find and play with them when they are present, and they are luminescent at night. These stingless jellyfish feed on small plankton and each other and are another transient in the seagrass community.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

There are certainly species of jellyfish to be aware of and avoid. But as you look deeper into this group there are harmless and fascinating members as well. Most of these Hydra are very small and hard to see while snorkeling, but they are there. Another creature to try and find while you are exploring and play “seagrass species bingo”. Have fun and stay safe.

1

1by Rick O’Connor

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.