Fecal pollution can pose major health problems for those who live and play along the Gulf of Mexico. It also can be disastrous for local economies that depend on tourism. This issue is of increasing concern around Pensacola Bay, Florida, where beautiful beaches and a thriving tourism industry draw visitors from far and wide. However, new research from the UF/IFAS Department of Soil, Water, and Ecosystem Sciences (SWES) shows there is a hidden threat to both human health and the environment. Fecal contamination of estuaries, creeks, and streams that feed into the bay is a significant challenge.

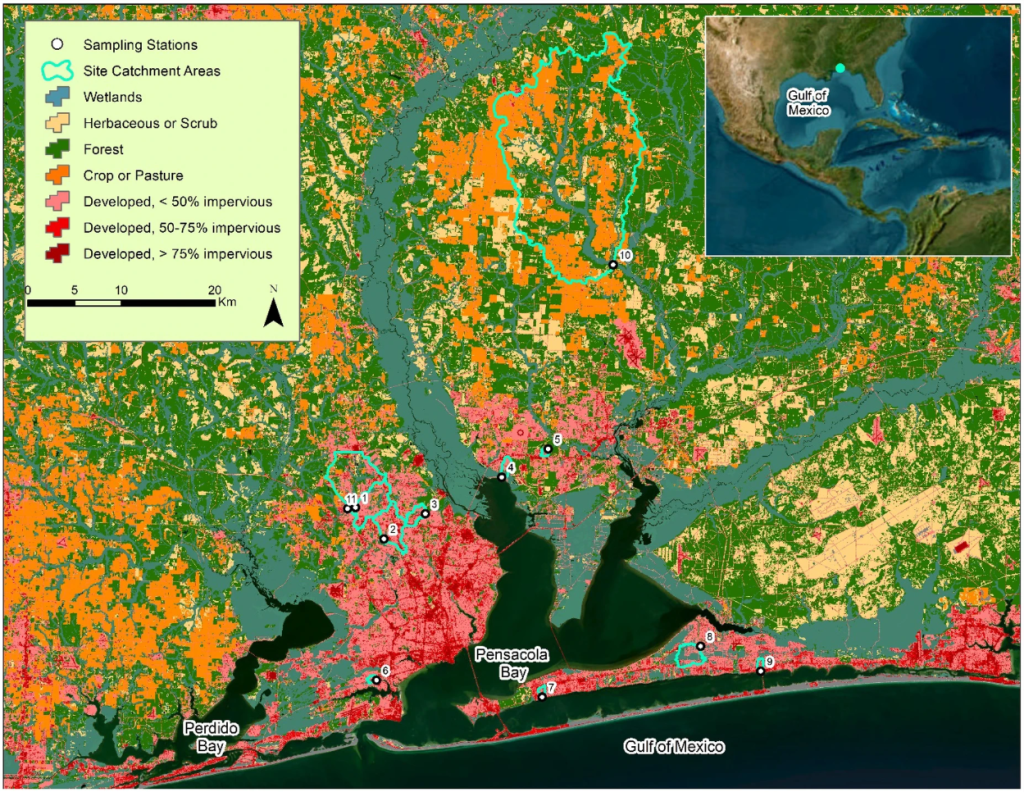

A recent study set out to quantify the presence of fecal indicator bacteria (FIB), particularly Escherichia coli (E. coli), in surface waters. Additionally, it aimed to determine the sources of this contamination. The study examined locations in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties.

“We wanted to distinguish between human and animal origins,” said Ronell Bridgemohan, a SWES doctoral candidate, whose dissertation research is the basis for the study. “We collected water samples from several creeks during two sampling periods in February 2021 and January 2022.”

Results

E. coli levels at six sites over the two-year period exceeded the safety threshold, with one site more than doubling the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s allowable maximum threshold.

“While many sites had high levels of bacteria, they were often not contaminated with human sewage and dog waste,” Bridgemohan explained. “We anticipate that these sources of FIB can be attributed to feral cats and other wildlife. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimates the number of stray and feral cats roaming the state is in the millions.”

Still, source tracking revealed that human and dog fecal contamination was widespread, affecting four of the nine sites. However, it’s worth noting that sites with those identified sources had E. coli levels below the impairment thresholds. Likewise, below-threshold level contamination from birds was identified at one site.

Implications

This research sheds light on the use of microbiological fecal source tracking (MST) in assessing bacterial inputs to water bodies. While FIB alone cannot pinpoint the pollution source, MST allows for more precise risk assessments. The use of both can lead to the development of effective mitigation strategies.

“It’s important to recognize fecal pollution doesn’t have a single source. It can result from various environmental conditions, including heavy rainfall, surface runoff, and contributions from both point and non-point sources,” Bridgemohan said. “Also, soil and stream sediments can store fecal bacteria, allowing them to survive and reproduce, and then release them, especially during runoff events.”

He said the study’s findings underscore the need for ongoing monitoring and management of fecal pollution in the Pensacola Bay watershed system.

“The results from this study have set a good baseline for us,” said Matt Deitch, SWES assistant professor of watershed management. “We already are collaborating with other scientists on more robust measurements and identifying different sources of fecal matter. Figuring out the animal sources can help us develop strategies to reduce the amount of it in our bays and beaches.”

The researchers hope current and future findings will help policymakers develop mitigation protocols. Efforts to reduce or eliminate fecal contamination would only help tourism-dependent, coastal communities.

The research is published in the journal Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. You can read the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-11478-1

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.