This time of year is surrounded with creepiness—October is full of haunted houses, scary costumes, and spooky music. Halloween and the Day of the Dead are, at their essence, times when we reflect on the relationship between life and death. Ancient traditions say this is a time when the division between the worlds of the living and dead are thinnest, and we can interact with those who have passed.

Even in the plant world, we see examples of this eerie interaction. Once known as saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), members of the plant kingdom called ghost plants (Monotropa uniflora, also known as corpse flower or Indian pipe), have a complicated relationship with the dead. In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. The original assumption was that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi—they even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. Many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, and mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding) like ghost plants actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi to take their nutrients.

Ghost plants grow in temperate regions of Asia and South America and throughout the United States (except in the southwest and Rockies), although they are a somewhat rare find. The plants do not produce chlorophyll, so they are mostly a translucent shade of white with some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms. Adding to its bizarre affect, the plant will break down and melt when touched. Ghost plants are true plants and members of the blueberry family—if you look at the flower structure, you can see their similarities. The plants are frequently found near beech trees and are pollinated by bumblebees and flies.

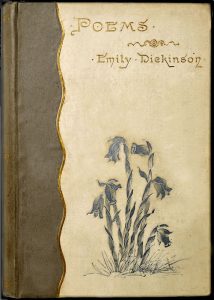

Cherokee legends include the ghost plant in their lore, likening a cluster of Indian pipe plants to great chiefs trying to resolve a quarrel and while gathering to smoke a peace pipe. The famed poet Emily Dickinson was also a fan of the plant, featuring it on the cover of a book of her poetry and calling it, “the preferred flower of life.” Scholars of Dickinson’s work believe she found the plant so meaningful precisely because of its fragility, rarity, and dependence on others.

This fall while you explore the forests around you, be sure to look down—you just might see a ghost–or perhaps a nutrient-sucking vampire!

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.